Professional Piano Pointers

By J. Lawrence Cook Criticisms and suggestions are welcome, and all communications addressed to the

writer in care of the INTERNATIONAL MUSICIAN will receive his personal attention Styles of popular piano playing are, in my opinion, to be regarded from two separate points of view, one based chiefly on the type of material used to produce certain varieties or shades of rhythmic effect and the other on finer development in execution wherein the mechanical aspect is taken so much for granted that one is but faintly aware of its existence as such.

In the former the listener is “carried”, and in the latter he is “sent”, so to speak. The former dictates a pattern of rhythmic impulse which pulls the listener along with it; while the latter, bordering more on the realm of the sublime, tunes in on the sense of higher artistic appreciation and forces itself to be felt, its rhythmic element being subconsciously absorbed. In one instance the listener need have but a primal sense of rhythmic reaction in order to be “carried” while in the other he must have not only that, but must, in addition, be “allergic” to the touch of genius.

The category of styles which motivates the first point of view may be compared with hats, shoes or other wearing apparel. This season the pianist whose style has most substantially captured the public fancy may be one who dotes upon carrying a baritone melody against some individualistic form of embellishment; next season the “boogie woogie” artists may be holding forth; and the next some other form may be in vogue. You may then adopt, accept or reject as you see fit, somewhat as you would seasonal styles in clothes. This is not true of the other type of piano playing, for, once it is set, it goes on and on without any appreciable change. Once a pianist has reached a satisfactory degree of proficiency in it, he can no more successfully change it than he can change his own personality; and the most faithful of his audiences are to be found mainly among musicians themselves.

So much for abstraction. Let us now get down to cases. However, since we did start with abstractions, suppose we group our concrete classifications accordingly, calling the first Number One and the second Number Two. NUMBER ONE When the average prospective student of modern popular piano playing walks into a studio to inquire about lessons, he usually opens his part of the interview somewhat as follows, provided that he has professional aims:

“I studied piano for about a year and a half. Having had no desire to become a classical pianist, I discontinued my regular lessons and turned to ‘swing’. After having gone to every studio of popular piano playing I could find, I was unconvinced of the capability of any to teach me just what I wanted to learn; so I bought some books and proceeded with self-study. I’ve picked up some ideas here and there and, adding these to what I learned from the books and to what I figured out myself from studying player rolls and phonograph records, I guess I haven’t done so badly. I play in a small band and am considered pretty good as a band pianist. However, I’ve often been told that I have no particular style and that I’m weak when it comes to taking solos. What can YOU do for me?”

The solution of at least some of the problems of such a prospective student lies in his first picking out several outstanding pianists whose styles he likes and studying the things they do, not limiting his observations to the mere structural texture of their tricks, but giving considerable attention to the manner of execution. There should be among these one special favorite whose style he likes best of all, and he should REALLY concentrate on him. This favorite should, in particular, have a clear-cut style which he is capable of handling with absolute mastery.

The object in making a study of several is not only to learn a wide variety of new tricks, but eventually to consolidate their methods in ways best suited to your own mechanical, technical and temperamental qualifications. You will have to be specific, too. That is, you must compile an actual repertory of what each has at some time or other done with a movement from one specific chord to another, in a given tempo and with a certain type of melody. Such exact information should be perpetuated by being recorded on manuscript or thoroughly committed to memory. You will finally “boil things down” to a point that suits you exactly in every way. When you begin to make practical use of devices so learned, you will find that your performance will begin to be different, whether or not you have made alterations in the actual structure. That is, even though you may make use of identical notes, there is bound to be an inflection provoked by your individual treatment, noticeable perhaps in no other way than by difference in shade of expression given to but a single note in an entire figure or phrase.

Continue along this line, making it a point to be always improving the quality of your bass tenths, your treble octaves, thirds and single-notes, and your runs. You will find that the ultimate rhythmic effect is usually a determining factor in the popularity of a given style. For example, the so-called “boogie-woogie” style is totally uninteresting harmonically; but it generates a rhythmic effect that is distinctive and different and which will cause even a critical ear to endure the monotony of its harmonic platitudes. Thus, “boogie-woogie” has swept the country. It is a fad, and will go as other fads come and go. It was with us more than 20 years ago, and, after having run its course this time, is bound to recur again in the future.

I recommend direct imitation at the start. As a matter of fact, some students may at first be so lacking in creative ability and even in adaptation that no other course will be feasible. Does not the future painter or sculptor seek to reproduce works of the old masters before he expects to make any headway toward achieving a style of his own.

The real signature of your style, once you have developed it, will be your excellency in performing one or two tricks which you have perfected for certain types of chords or resolutions. Some pianists are known by their individual treatment of certain types of runs and others for their solid rhythm; some for their smooth execution of bass tenths, and others for their interesting contrapuntal bass movements; some for excellency in fast playing, and others for the same in slow playing.

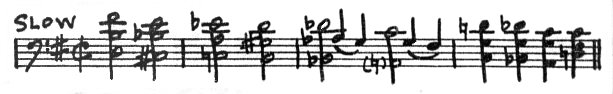

Can you name the well known pianist who should be readily identified with this type of run?

(Continued on Next Page) PROFESSIONAL PIANO POINTERS (Continued from Preceding Page) NUMBER TWO Those in this group are to popular piano playing what a finished classical artist is to classical playing. I refer, of course, to the classical artist who has achieved distinction as a soloist. Albeit, the popular artists whom I place in this group all have a good background in classical study. Seldom do they win popularity polls, though, for theirs is a style without appeal to the masses. One outstanding feature of their assets is their fineness of touch, which is of minor importance to those listeners who respond more readily to the appeal of rhythm than to that of tonality.

True enough, the stylists to whom I now refer have much in common with the adherents of the other style (Number One), but aside from fineness of touch, they are required to exhibit superior technique as well as an almost phenomenal aptness at improvising.

The final impressions produced in this classification of style may generally be referred to as either CONTRAPUNTAL or PEDAL-WISE. The contrapuntal is identified by the ultimate effect of single-note movements in the right hand part and legato-like movements of bass tenths in the left. The general reaction is that you feel like swaying or just drifting along. The flow of music seems to travel, as it were, from east to west.

The pedal-wise form is noted by a sort of up-and-down impression. That is, the listener is more strongly conscious of movements of the performer’s hands from an upward position down to the piano keys. Fundamental pulsations in bass are prominent and treble figures are rather strongly accentuated whether they be of solid or moving character. It is easy to understand how this form lends itself to dancing purposes, while the contrapuntal is the more satisfactory for relaxed listening.

I should like my readers to listen to a good solo recording by Teddy Wilson and one by “Fats” Waller. Close your eyes as you listen to each, and make a note of your general reactions in respect to contrapuntal and pedal-wise “listening impression.” I should be pleased to have you write in your classifications.

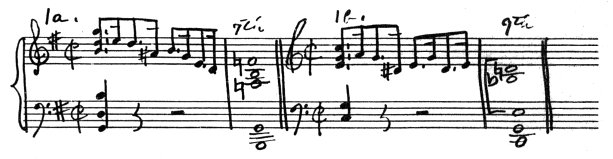

The three examples which follow

show what three stylists have done with the second four measures of “Honeysuckle Rose” in various recordings. It is well to note that each abandons the melody and proceeds to insert original figures to fill out these measures.

The first is a case of pure improvistation, the second a case of stock figuration against a specific harmonic pattern; and it is logical to assume that in the third the artist worked his figure out well in advance of the recording.

Can you identify the artists by playing over the measures shown? If not, I shall be pleased to honor your request not only for the names of the artists, but for the makes and numbers of the records on which the measures have been recorded. Note: The hand-writen manuscript examples shown in the article above are by J. Lawrence Cook.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()