Such are the bare facts of the life of Ferdinand Joseph Lamothe — better known as Jelly Roll Morton, one of the most towering figures in the history of American popular music. This flawed document doesn’t even hint at Morton’s lasting contributions to our nation’s culture — the hundreds of songs he composed, the piano style he pioneered, the many musicians he inspired. The certificate does contain a couple of noteworthy errors: Morton’s actual birthdate was October 20, 1890, and his father’s name was Edward J. Lamothe (Edward Morton was his stepfather).

The last name on the document often goes unrecognized, but it carries considerable weight. Anita Gonzales inspired at least two of Morton’s compositions: “Sweet Anita Mine” and a subtle tango called “Mama ‘Nita.” The sister of pioneering clarinetist-drummer-pianist Oliver (Ollie) “Dink” Johnson, she was a beautiful Creole woman whose relationship with Morton dated back many years — probably to the very beginning of the twentieth century, before his departure from New Orleans. Gonzales also played an influential role in the jazzman’s life in California after World War I, a thinly documented period of his career. She was with Morton in his last days and was one of the last people to see him alive. Though she is listed as the pianist’s wife, researchers have never found conclusive proof they were actually married.

Most jazz fans are familiar with the story of Morton’s triumphant emergence from Storyville’s brothel parlors. He achieved great prominence and wealth as leader of the famous Red Hot Peppers, probably the most thrilling recording group in the history of New Orleans music. Never known for his modesty, Morton walked around with a stash of $1,000 bills, carried diamonds in every pocket, and proudly claimed (with considerable justification) that he personally invented jazz. His business card pompously announced:

JELLY ROLL MORTON – ORIGINATOR OF JAZZ AND STOMPS

VICTOR’S No. 1 RECORDING ARTIST

WORLD’S GREATEST HOT TUNE WRITER

|

|

During the 1920s Morton achieved unprecedented success and notoriety, but his rapid rise was followed by an equally rapid downfall. By 1930, the Jazz Age was nearing its end. Victor did not renew Morton’s recording contract, and bookings for his Red Hot Peppers slowed, then stopped completely. Jazzmen struggled to compete for the few entertainment dollars available in the Depression, and by 1934 Morton was down to his last diamond, a half-carat gem imbedded in his front tooth.

That year he endured the embarrassment of playing on an inferior Wingy Manone recording date for Columbia; his uninspired piano solo is heard briefly on the tune, “Never Had No Lovin’”. Wingy neglected to mention Morton’s name as he happily introduced such unlikely sidemen as Artie Shaw, Bud Freeman, and John Kirby. Columbia wisely chose not to issue the records until twenty years later, when they appeared on the company’s Special Edition collector’s series.

The burgeoning swing craze put a final coda to Morton’s golden era, and small groups such as his Red Hot Peppers seemed dated to younger listeners. Ironically, they acclaimed the popular swing versions of Jelly’s tunes and riffs beings recorded by most of the popular bands.

“F. Morton” appeared in tiny print beneath the song titles on millions of records, but the public paid no attention to the composer credits. Morton never received proper compensation for his huge-selling compositions; a disagreement with his publishers and ASCAP limited his royalties.

Morton knew he had helped create the big-band sound, but he never received due credit. Desperate, bitter, and in failing health, he resurfaced briefly in 1938, playing for a few faithful followers at the Jungle Inn, a seedy club over a hamburger stand in Washington, D.C. His historic Library of Congress recordings led to a final Victor date in 1939, which brought a brief flurry of renewed recognition, and the General Record Company timidly released several Morton piano solos and some band numbers; but poor marketing, coupled with public apathy, severely limited the success of these offerings.

In 1940, with music still surging through his productive mind, Morton decided to move to Los Angeles, hoping to regain his health and rejuvenate his career. In Mister Jelly Roll: The Fortunes of Jelly Roll Morton, New Orleans Creole and “Inventor of Jazz,” Alan Lomax described the pianist’s cross-country journey. Morton made the trip in his battered Lincoln, towing his Cadillac behind on a chain. Forced to abandon the Lincoln in an Idaho snowdrift, he continued in the Cadillac, which was loaded with clothes and a scrapbook filled with faded mementos. He also brought with him a dozen new big-band arrangements that he planned to record with fellow New Orleans expatriates Kid Ory, Mutt Carey, Bud Scott, Ram Hall, and Ed Garland.

After Morton arrived in Los Angeles, Garland assembled this illustrious group and rented the Elks Hall on Central Avenue for rehearsals, but the pianist’s physical condition had seriously deteriorated. He valiantly attended the sessions but had his former pupil, Buster Wilson, stand in for him at the piano. But if Morton’s body was failing, his musical mind was as sharp as ever. “Jelly’s arrangements were very interesting,” Ed Garland told me. “He knew that the popular swing bands were playing his songs. Benny Goodman’s record of ‘King Porter Stomp’ and Hampton’s ‘Shoe Shiners Drag’ were heard daily on the radio. He wanted to show those bands how his music should be played.”

Unfortunately, the recording date never took place; Morton died on July 10, 1941. The golden era of our music heard the last of Jelly’s creativity — and the world hardly noticed.

An ironic twist of fate denied an opportunity for me to own the arrangements Morton wrote for his anticipated record date. His hand-written scores remained in Buster Wilson’s front room for almost a decade. They were in a large trunk draped with a silk shawl on which stood a tarnished brass lamp. Buster promised to sort through the trunk “one day” and offered to give me those old manuscripts.

I repeatedly reminded him of his offer, but he never managed to open the trunk. After Buster’s death, I informed his widow, Carmelita, of his promise. I discreetly called her several times, but she seemed reluctant to let me have the arrangements. The phone eventually was disconnected. Carmelita moved. She apparently left the city, and I was unable to contact her again.

With that I gave up all hope of ever locating these historic scores, and they remained lost for decades. They finally resurfaced in the 1990s, as reported by Phil Pastras in Dead Man Blues. The thirteen-piece big-band arrangements were found among the huge catalogue of material left by Bill Russell to the Historic New Orleans Collection. An orchestra assembled by Don Vappie performed four of these compositions at the 1998 New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival.

Two witnesses to the event, musician Jacques Gauthé and writer Barry McRae, both praised Morton’s apparent mastery of the big-band idiom, and both commented on the “modernism” of one particular piece, “Gan-Jam.” McRae compared it to the work of Charles Mingus, Gauthé to that of Stan Kenton.

The private recording of the event verifies that the piece is indeed very modern in conception. Morton recorded two of the pieces — “Mister Joe” and “We Are Elks” — in earlier forms, and they contain no great surprises. “Oh! Baby,” by contrast, sounds like a contemporary (circa 1940) swing arrangement, and the great surprise, “Gan-Jam,” looks forward at least ten years in its bold use of dissonance and eastern modal scales.

The style of the group Vappie assembled is New Orleans Revival; one wonders how much more modern the arrangements might sound if played by a more contemporary group.

It is regrettable that Jelly Roll Morton’s last days were such sad ones. He spent them trying to pull himself out of obscurity and reclaim his rightful position as one of the nation’s most important and accomplished musicians. The man who claimed to have invented jazz simply faded away.

When they buried Jelly Roll Morton in Calvary Cemetery in east Los Angeles, the diamond was missing from his front tooth. Pallbearers included Kid Ory, Mutt Carey, and Ed Garland. David Stuart of the Jazz Man Record Shop was the only white man attending the Catholic funeral. A story in Down Beat magazine reported that Duke Ellington and Jimmy Lunceford, the two most prominent black bandleaders of the day, were noticeably absent from the burial services. Ellington was appearing at the Mayan Theater in his production “Jump for Joy,” and Lunceford and his band were booked at the Casa Mañana in nearby Culver City.

Jelly’s grave — Number 4, Lot 347, Section N — lay on a gently sloping grass-covered hill. It remained unmarked and unattended, and the music world seemed to forget the genius buried there. Nine years later, tall weeds had overgrown the grave, and the surrounding area was badly neglected. Apparently, perpetual care fees had not been paid.

Early in 1950, members of the Southern California Hot Jazz Society decided to raise the funds for a marble identification plaque and perpetual care. We reserved the Maynard Theater on Washington Boulevard for a September 30, 1950, benefit concert, then set about lining up performers. Blues singer Monette Moore, a contemporary of Bessie Smith’s, volunteered to appear. Albert Nicholas, Zutty Singleton, and Joe Sullivan joined the bill. Young Johnny Lucas, original trumpet player in the Firehouse Five Plus Two, also offered his services. To assure a full program worthy of the sixty-cent admission price, we also invited Conrad Janis’ Tailgate Jazz Band, winners of Record Changer magazine’s amateur band contest in 1949.

Bob Kirstein and I — SCHJS vice president and president, respectively — both hosted weekly radio shows on a small FM station, and we took advantage of our air time to advertise the event. Ticket sales were slow at first, but by mid-September we knew there would be a full house.

That’s when Anita Gonzales appeared on the scene.

The radio station manager received a phone call from a woman identifying herself as Jelly Roll Morton’s wife. Why, she demanded to know, was his station publicizing an event to raise money for her husband’s gravestone? She sounded irate and insisted the activity be halted immediately.

Kirstein and I apprehensively returned Anita’s call. She emphatically informed us she would not allow the Jazz Society to buy the marker. In fact, she intended to purchase the plaque herself and would not condone a charitable effort that would embarrass the memory of her departed husband. To placate her, we asked if we could meet her in person. We hoped to persuade her that our project was a sincere tribute from Morton’s fans and in no way could be construed as “charity.” We resisted the temptation to ask why she had waited ten years to make the purchase — and why the grave was not properly maintained.

Gonzales invited us to visit her the following day at the Topanga Beach Auto Court, a small motel she operated on Pacific Coast Highway in nearby Malibu Beach. She greeted us with a friendly smile and introduced us to her husband, J. F. Ford. Despite the acrimonious tone of her telephone conversation, she seemed genuinely pleased to see us. A large, pretty woman, she spoke in warm tones with an accent reflecting her New Orleans heritage. A portable record player and several albums stood on a bookcase near the door; I wondered if the stack included any of Morton’s rare old records. A large theatrical blowup of a nearly nude girl hung on one wall. Noticing my interest, Gonzales said: “That’s my daughter. Her name is Aleene. She’s a striptease dancer at the Follies Theater.”

“I’m fixing a batch of fried chicken,” she continued. “Would you please stay and have some? I’m famous for my fried chicken.” She brought us each a plate of steaming fried chicken and a cold bottle of beer. As we munched the delicious food, she reminisced about her years with the great Jelly Roll Morton: I used to sing, you know. Not really as a professional — but I had a good voice and knew all of the old songs. I pleaded with Jelly to let me sing with his band, but he never would. He was very old-fashioned. He didn’t want me to work. When I ran a hotel years ago — in 1918, I think — he made me hire people to clean and rent the rooms. He refused to allow me to do any of the work.

We were sweethearts years ago back in New Orleans. My brother, Dink Johnson, reintroduced us here in L.A. before the first World War. Dink was playing drums with Freddie Keppard and the Creole Band at the Orpheum Theater. He lives in Santa Barbara now, but I seldom see him.

Jelly and I traveled a lot in those days. We went up the coast to Oregon for several months — even into Canada. Everywhere we went, people loved his music. Did you know he wrote a tune for me? I used to have many of Jelly’s records, but most of them were broken over the years. He made a record here in Los Angeles long ago, but I don’t know if it ever came out. Jelly did a lot of recording after he left to go back east. He sent many of them, but they usually arrived cracked.

I hesitated to interrupt her recollections but finally generated the courage to broach the subject of Morton’s grave. I reminded her that the SCHJS concert was only about a week away and said that, because we had publicized the event as a fundraiser for the marker, we felt obligated to spend the money for that purpose. Gonzales’ mood changed, and she became quite adamant. “I cannot allow strangers to buy the stone for my beloved. Tomorrow I plan to visit the cemetery and purchase the plaque. I’ll have it no other way.” From the tone of her voice, it seemed evident she was determined to halt the project we had worked so hard to complete. “I realize you are trying to do something good,” she added, “but Jelly would never forgive me if I allowed this to happen.”

Bob Kirstein suggested perhaps the SCHJS could give her the proceeds from our show. If she used those funds to make her purchase, we would have fulfilled our objective. She refused. We told her that all the tickets were sold, and it was not possible to cancel the benefit. The patrons and the musicians expected all profits to go toward the purchase of Jelly’s grave marker. Gonzales shook her head and said, “I’m buying the plaque tomorrow.”

She eventually agreed to a let us put a second identification on the grave; that way, we could satisfy our commitment to spend the money on a Morton marker. But the next day, Calvary Cemetery informed me that it permitted just one identification per grave. So we were back to square one.

With the concert date now so close, it was too late for a cancellation; we had no choice but to continue as planned. Kirstein had invited Gonzales to appear on his next broadcast, and we hoped he might be able to change her mind and gain her support.

The radio interview, interspersed with Morton’s records, went quite well. “You know,” Gonzales remarked after listening to Morton’s “New Orleans Joys,” “he had a special touch that was unique. Somehow, when Jelly played, he got a different sound from the piano — maybe it was because he loved the music so much.” After a long pause she said, “The world has forgotten him, but I always remembered what he accomplished. Without Jelly, we’d still be doing the waltz. He mixed all music together — rags, symphony, marches. That’s how jazz started, and Jelly did it. Someday, he’ll get the credit.”

Gonzales spoke emotionally of Morton’s decline and death. “He expired in my arms,” she sobbed. “I cared for him . . . nursed him during a terrible illness. He came back to me when he knew his time was short. I was the only woman he ever loved.”

Recalling the last time Morton played in Los Angeles, Gonzales said: When he arrived the last time, he was too sick to play. He kept thinking he would get well enough to take some of the jobs he was offered. He never could take any of them.

I think the last time he actually played in L.A. was back around 1936. Jelly came here with a colored burlesque show called “Brown Skin Models,” and they played at the Burbank Theater on Main Street, down on Skid Row. The girls didn’t strip. They did a lot of motionless posing behind a sheer curtain. It was quite risqué at the time. Peg Leg Bates was the headliner; Jelly’s name was not advertised. He only played in the pit and never soloed. What a waste! But those were the Depression years, and Jelly was glad to have the work.

Jelly Roll Morton (third from left) in 1921,

Cadillac Cafe, Los Angeles.

The famous entertainer Ada “Bricktop” Smith is at Jelly’s left. This is probably the first reference to Morton’s participation in “Brown Skin Models,” a seedy touring company of black artists who played second-rate burlesque theaters in the 1930s. My great-uncle, the late Jack Rothschild, co-produced the show with his partner Irvin C. Miller (brother of Flournoy Miller, a member of the Miller and Lyles vaudeville team of the 1920s). As a high school student, I saw the show during its various stops in Los Angeles. On one trip, Uncle Jack booked the Models for a week at the Million Dollar Theater. Knowing of my budding interest in jazz, he invited me to hear the new piano player in the show — Jelly Roll Morton. At the time, however, I was more interested in Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, and Tommy Dorsey. So, to my everlasting dismay, I did not take advantage of the opportunity to see — and, probably, to meet — the great Jelly Roll Morton.

After Kirstein’s radio program concluded, Gonzales reached into her purse and handed me a gift. It was an envelope containing a brittle sepia photograph of Morton. “That was taken before 1914,” she told me. “I am sure of the date because the picture is of Jelly in blackface with Rosa, his partner in a vaudeville act he left in 1914.” On the back of the old photo, written in Morton’s bold hand, were the words: “Ferd and Rosa to Dear Godmother Laura Hunter. Chicago.”

Jelly Roll Morton (at right)

with his vaudeville partner, Rosa We had made arrangements to take Gonzales to Mike Lyman’s, where Kid Ory was appearing with his Creole Jazz Band. As we were leaving the studio, she suggested that we take her car, which was parked at the curb. “How would you like to drive Jelly’s Cadillac?” she asked, handing me the keys. It was a beautiful 1938 sedan, long and black with maroon leather seats — the same car Morton drove during his move to Los Angeles ten years earlier. I eagerly slid behind the wheel, started the motor, and headed down Sunset Boulevard. Driving Jelly Roll Morton’s car was one of my greatest thrills. The trip to Lyman’s was very short, and I hated for it to end.

During a break between sets, Ory’s band came to our table. Naturally, the subject of Jelly Roll Morton dominated our conversation. “He was a very tough man to work for,” recalled Ory, who played on many of Morton’s Red Hot Pepper recordings. “He knew exactly what he wanted and would not permit any variation from his arrangements. They were tough to play — the tempos were difficult, lots of key changes. But he was always right; the records sounded great.”

Throughout the discussion, Ram Hall looked very perplexed. Later he called me aside and said, “That’s not Mrs. Morton! I used to go to her house in New York for gumbo — but that’s not the same woman! Who is she?” Kid Ory repeated Hall’s observation: “I never saw that woman before in my life. I knew Jelly’s wife very well. Why did you bring her here and introduce her as Mrs. Morton?”

Apparently, Ory and Hall were referring to Mabel Bertrand, a former dancer at the Plantation Cafe in Chicago who lived with Morton from 1927 until his 1940 move to California. Morton immortalized this woman with a brilliant Victor recording titled “Fussy Mabel,” and Ory and Hall must have thought she was his wife.

From the data on Morton’s death certificate, Anita was with him when he died in Los Angeles a decade earlier. Why did Ory and his band not remember seeing her during those last rehearsals of Morton’s big band arrangements? This is a question that will probably never be answered.

We left the club and drove back to the radio station. On the way, I made a final plea for permission to place a marker at Morton’s gravesite. “I ordered the plaque yesterday,” she snapped. “And it will be placed on the grave next week.” Her decision was final. The evening ended with her dismal announcement; she left us at the station and sped off in Jelly’s old car. That was the last time we saw Anita Gonzales.

It was too late to cancel our benefit concert, so we held it as scheduled. The event was a great success; a capacity audience enjoyed an evening of outstanding music, and we raised several hundred dollars. SCHJS treasurer Bill Miskell quietly deposited the proceeds in a bank account titled, “The Jelly Roll Morton Fund.” It remained untouched, gathering interest for many years. In 1966 we were saddened by the death of Johnny St. Cyr, who played banjo on many of Morton’s Red Hot Pepper recordings. St. Cyr had moved to Los Angeles in 1955, made many friends among the jazz fraternity, and eventually became president of SCHJS. We decided to use the sixteen-year-old Jelly Roll Morton Fund to purchase Johnny St. Cyr’s tombstone. Out of respect for Flora St. Cyr, Johnny’s widow, this benevolent act was never publicized; it is revealed here for the first time.

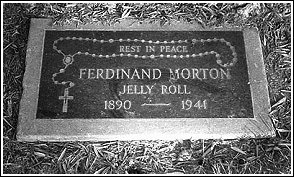

Anita Gonzales followed through on her promise to purchase a headstone for her husband’s grave. Bob Kirstein and I went to see it a few days after the Maynard Theater concert. As we climbed the slight knoll toward the grave, we noticed the neatly trimmed grass and a fresh bouquet in a bronze urn. A handsome plaque gleamed brilliantly in the afternoon sun. Carved into the black marble were the words:

FERDINAND MORTON

JELLY ROLL

1890 — 1941 We placed a large garland of flowers next to the new marker. The gold letters on the bright red ribbon read, “MR. JELLY ROLL”. We took several photos and left the cemetery, comforted with the knowledge that the extraordinary musician’s grave was finally suitably marked.

I learned later that Anita Gonzales died April 24, 1952, about a year and a half after our encounter. Her death certificate indicates that she, like Morton, is buried in Calvary Cemetery.

Jelly Roll Morton’s influence on the world of jazz is still strongly felt. Maybe he did not personally invent jazz, as he claimed, but his great and everlasting contributions to the art form cannot be disputed. With the possible exception of Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton was the most creative figure in the history of New Orleans jazz. © 2000 Floyd Levin

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()